Worldview Conflict

Figure 1 from Brandt & Crawford, 2020

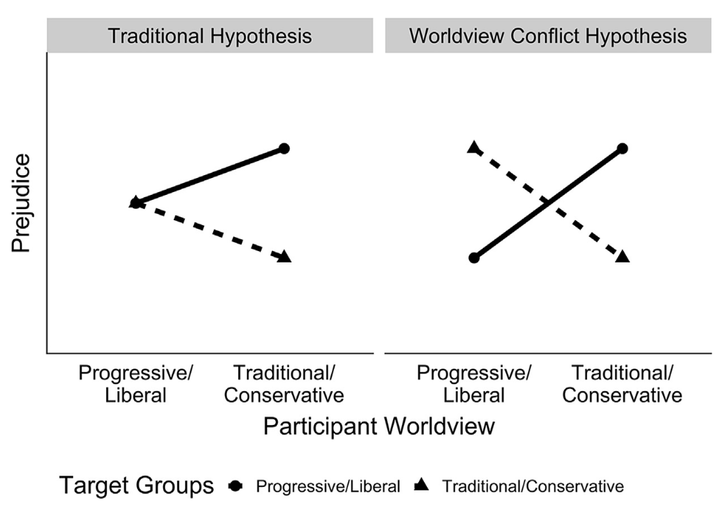

Figure 1 from Brandt & Crawford, 2020The worldview conflict hypothesis (Brandt & Crawford, 2020) builds on the decades-old idea that people are motivated to defend their deeply cherished beliefs. Expressing animosity towards people and groups who do not share their beliefs is one method people use to defend their beliefs. We initially tested this idea in the political realm, finding that both liberals and conservatives express animosity towards groups who are seen as violating their moral values (e.g., Brandt, 2017; Brandt et al., 2014; Crawford, Brandt, et al., 2017; Wetherell, Brandt, & Reyna, 2013). We found similar results when we expanded to religion, finding that both the religious and non-religious express animosity towards groups who violate their moral values (e.g., Brandt & Van Tongeren, 2017; Van Tongeren, Kubin, Crawford, & Brandt, 2020). Crucially, although the targets of this animosity are meaningfully different, common psychological mechanisms of perceived worldview and value dissimilarity that account for group-based animosity cut across different strata of society.

This work is practically important because it suggests that to overcome the societal disfunction that comes with polarization, we need to understand how people perceive and cope with value differences. It is theoretically important because dominant models of political ideology and religiosity make a different prediction. They predict that people with more traditional belief systems are more likely to be express group-based animosity compared to people with more liberal or progressive belief systems. Scholars make this prediction because people with more traditional worldviews tend to be less open to experience and prefer more structure than people with more progressive worldviews. These individual differences should cause people with more traditional worldviews to express more animosity. Our work shows that these dominant models do not account for the data. Moreover, we find that even people high in openness also express animosity towards groups who violate their values (e.g., Brandt et al., 2015; Crawford & Brandt, 2019). Animosity towards people who violate our values appears to be a common psychological process.

Key Project Publications

- Bergh, R. & Brandt, M. J. (2023). Generalized prejudice: Lessons about social power, ideological conflict, and levels of abstraction. European Review of Social Psychology, 34, 92-126. doi | pdf

- Bergh, R. & Brandt, M. J. (2022). Mapping principal dimensions of prejudice in the United States. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 123, 154–173. doi | pdf

- Brandt, M. J. (2017). Predicting ideological prejudice. Psychological Science, 28, 713-722. doi | pdf | code | data

- Brandt, M. J., Chambers, J. R., Crawford, J. T., Wetherell, G., & Reyna, C. (2015). Bounded openness: The effect of openness to experience on intolerance is moderated by target group conventionality. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 109, 549-568. doi | pdf | code

- Brandt, M. J. & Crawford, J. T. (2020). Worldview conflict and prejudice. In B. Gawronski (Ed.) Advances in Experimental Social Psychology, 61, 1-66. doi | pdf

- Brandt, M. J. & Crawford, J. T. (2019). Studying a heterogeneous array of target groups can help us understand prejudice. Current Directions in Psychological Science, 28, 292-298 doi | pdf

- Brandt, M. J., Crawford, J. T., & Van Tongeren, D. (2019). Worldview conflict in daily life. Social Psychological and Personality Science, 10, 35-43. doi | pdf | code | data

- Brandt, M. J., & Crawford, J. T. (2016). Answering unresolved questions about the relationship between cognitive ability and prejudice. Social Psychological and Personality Science, 7, 884-892. doi | pdf | code

- Brandt, M. J., Reyna, C., Chambers, J., Crawford, J., & Wetherell, G. (2014). The ideological-conflict hypothesis: Intolerance among both liberals and conservatives. Current Directions in Psychological Science, 23, 27-34. doi | pdf

- Brandt, M. J. & Vallabha, S. (2025). Intraindividual Changes in Political Identity Strength (but not Direction) are Associated with Political Animosity in the United States and the Netherlands. Personality and Social Psychology Bulletin, 51, 828-844. pdf | code | data

- Brandt, M. J. & van Tongeren, D. R. (2017). People both high and low on religious fundamentalism are prejudiced towards dissimilar groups. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 112, 76-97. doi | pdf | code | data

- Cassario, A. L., Vallabha, S., Thompson, J. L., Carrillo, A., Solanki, P., Gnall, S., Rice, S., Wetherell, G. A., & Brandt, M. J. (2025). Registered report: Cognitive ability, but not cognitive reflection predicts expressing greater political animosity and favouritism. British Journal of Social Psychology, 64 e12814. pdf | code

- Colombo, M., Strangmann, K., Houkes, L., Kostadinova, Z. & Brandt, M. J. (2021). Intellectually humble, but prejudiced people. A paradox of intellectual virtue. Review of Philosophy and Psychology, 12, 353-371. doi | pdf | code | data

- Crawford, J. T. & Brandt, M. J. (2020). Ideological (a)symmetries in prejudice and intergroup bias. Current Opinion in Behavioral Sciences, 34, 40-45. doi | pdf

- Crawford, J. T., Brandt, M. J., Inbar, Y., Chambers, J. R., & Motyl, M. (2017). Social and economic ideologies differentially predict prejudice across the political spectrum, but social issues are most divisive. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 112, 383-412. doi | pdf

- Turner-Zwinkels, F. M., van Noord, J., Kesberg, R., Garcia-Sánchez, E., Brandt, M. J., Kuppens, T., Easterbrook, M. J., Turner-Zwinkels, T., Gorska, P. Marchlewska, M., & Smets, L. (2025). Affective polarization and political belief systems: The role of political identity, and the content and structure of political beliefs. Personality and Social Psychology Bulletin, 51, 222-238. doi | pdf | code

- Voelkel, J. G., Ren, D., & Brandt, M. J. (2021). Inclusion reduces political prejudice. Journal of Experimental Social Psychology, 95, 104149. doi | pdf | code | data