Belief System Dynamics

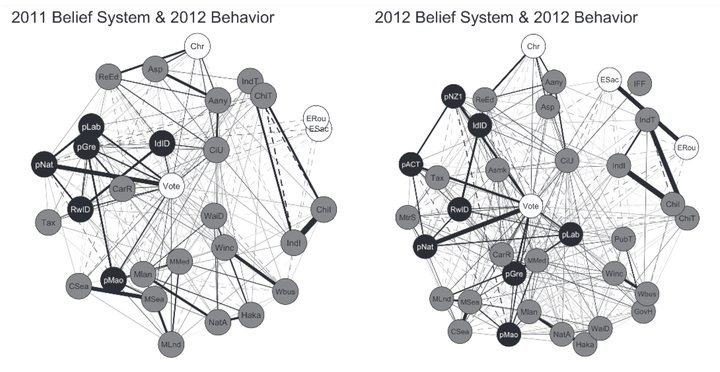

Figure 2 from Brandt, Sibley, & Osborne, 2019

Figure 2 from Brandt, Sibley, & Osborne, 2019The typical approach in the attitudes literature is to study one attitude at a time. What happens when we treat attitudes at interdependent, rather than separate entity disconnected from other attitudes and values? Our research on belief system dynamics does just this. In particular, we are testing how the connections between people’s attitudes and values – their belief systems – affect how attitudes develop and change.

As a first step, we used simulations to model these interdependences. These simulations implemented my idea that interconnected attitudes, values, and identities mutually influence each other with each person potentially having their own uniquely structured belief system. The strength and structure of the connections between the attitudes and identities in these belief systems determines the dynamics of the attitudes in the belief system. In our simulation work, this model accounted for several empirically known, but otherwise unrelated phenomena in the belief systems literature (Brandt & Sleegers, 2021). This model shows that disparate findings from sociology, political science, and psychology, that are typically studied and conceptualized separately from one another, can be explained by the same set of psychological processes.

Empirically, the lab documents the structure of people’s belief systems and how belief system structure is related to key outcomes (e.g. attitude change, belief extremity). Together, this work demonstrates that to understand attitude and value change, we need to understand the systems in which the attitudes and values are embedded. For example, the lab has found that liberals and conservatives have different moral value structure (Turner-Zwinkels, Sibley, Johnson, & Brandt, 2021) and that people’s political identities are particularly central to the organization of their political belief systems (Brandt et al., 2019; Turner-Zwinkels & Brandt, in press). These initial findings suggest that belief system structure matters for individuals. We also find that differences in belief system structure are important interpersonally: The political outgroups we dislike the most disagree with us on the issues and have belief system structures that are similar to our own (Turner-Zwinkels et al., in press).

The lab’s current projects have turned towards understanding how belief system structure influences persuasion. We are taking advantage of the fact that people often have differences in their belief system structures (Brandt, 2022), to test if these differences affect the success of persuasion attempts and the stability of attitudes over longer periods of time. In one project, we found that changing one attitude (the target attitude) can change other attitudes that are close in the belief system to the target attitude (Turner-Zwinkels & Brandt, 2022). In another project, we found that attitudes most and least central to the belief system are equally susceptible to persuasion (counter attitude theory; Brandt & Vallabha, in press).

Key Project Publications

- Brandt, M. J., Sibley, C., & Osborne, D. (2019). What is central to belief system networks. Personality and Social Psychology Bulletin, 45, 1352-1364. doi | pdf | code

- Brandt, M. J. (2020). Estimating and examining the replicability of belief system networks. Collabra: Psychology, 6, 24. doi | pdf | code

- Brandt, M. J. (2022). Measuring the belief system of a person. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 123, 830-853. doi | pdf | code | data

- Brandt, M. J. & Morgan, G. S. (2022). Between-person methods provide limited insight about within-person belief systems. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 123, 621-635. doi | pdf | code | data

- Brandt, M. J., & Sleegers, W. W. A. (2021). Evaluating belief system networks as a theory of political belief system dynamics. Personality and Social Psychology Review, 25, 159-185. doi | pdf | code

- Brandt, M. J. & Vallabha, S. (in press). Inter-attitude centrality does not appear to reduce persuasion for political attitudes. European Journal of Social Psychology. pdf | code | data

- Turner-Zwinkels, F. M. & Brandt, M. J. (in press). Ideology strength vs. party identity strength: Ideology strength is the key predictor of attitude stability. Personality and Social Psychology Bulletin. doi | pdf | code

- Turner-Zwinkels, F. M., van Noord, J., Kesberg, R., Garcia-Sánchez, E., Brandt, M. J., Kuppens, T., Easterbrook, M. J., Turner-Zwinkels, T., Gorska, P. Marchlewska, M., & Smets, L. (in press). Affective polarization and political belief systems: The role of political identity, and the content and structure of political beliefs. Personality and Social Psychology Bulletin. doi | pdf

- Turner-Zwinkels, F. M. & Brandt, M. J. (2022). Belief system networks can be used to predict where to expect dynamic constraint. Journal of Experimental Social Psychology, 100, 104279. doi | pdf

- Turner-Zwinkels, F. M., Sibley, C. G., Johnson, B. B., & Brandt, M. J. (2021). Conservatives moral foundations are more densely connected than liberals’ moral foundations. Personality and Social Psychology Bulletin, 47, 167-184. doi | pdf

- Van Noord, J., Turner-Zwinkels, F., Kesberg, R., Brandt, M. J., Easterbrook, M. J., Kuppens, T., & Spruyt, B. (in press). The nature and structure of European belief systems: Exploring the varieties of belief systems across 23 European countries. European Sociological Review. pdf